True Trials: How we went beyond industry standards to develop our own, better metrics

Published 2023-03-21

Summary - Want to boost your win rate? Here's how true trials provided us with the meaningful metrics we needed to track our progress and better convert prospects.

Metrics influence your company’s behaviour.

But they have to be the right metrics.

And what’s right for you isn’t necessarily what’s standard in your industry.

We’ve learned that it’s important to experiment with metrics so that you can develop measurements that are meaningful to you.

We had our own ‘Aha! moment’ when we changed our approach to the way we gather information about potential clients. By creating a new metric — something we call ‘true trials’ — we’ve vastly improved our ability to predict which prospects convert into clients.

And armed with that information, we now know where to focus our efforts to boost our win rate.

Here’s the story of how we did it.

The issue

We attract prospects and convert them into customers.

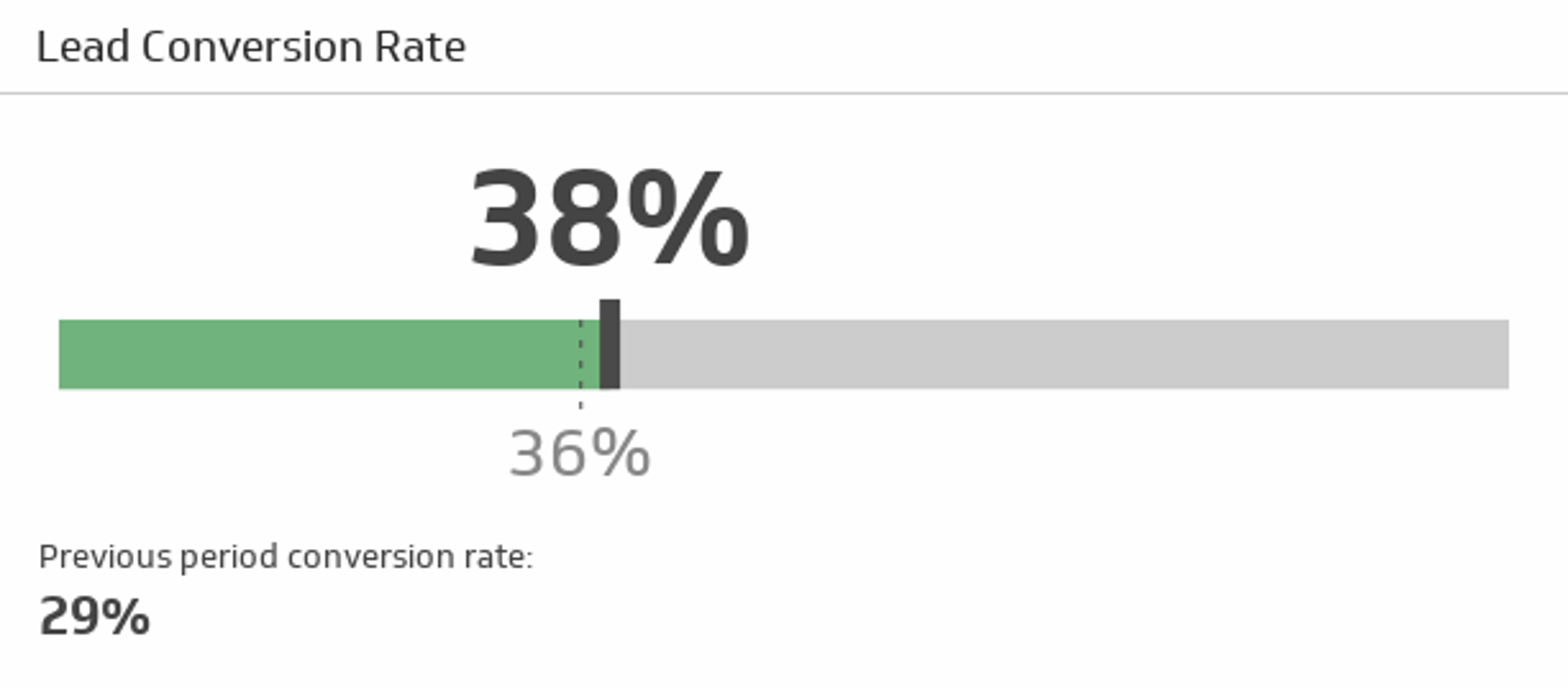

An industry standard metric for measuring success is the lead conversion rate: How many prospects convert into clients?

At first glance it may look like this is an easy thing to measure — and it is. But it likely won’t tell you much or drive the right behaviour.

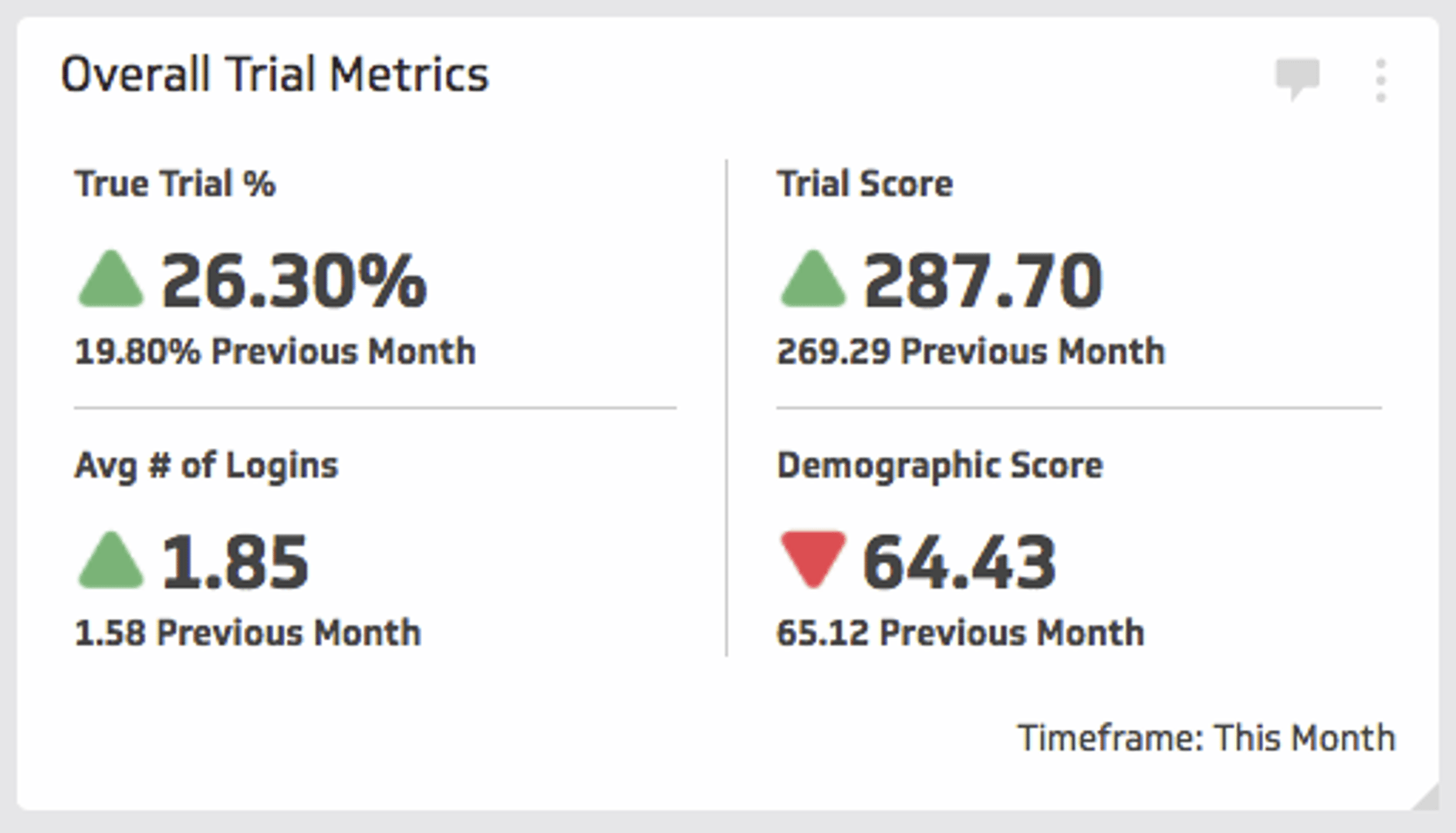

We were also using two other metrics to help us understand behaviour and lead quality — something called trial score (a tally of what features our trial users would interact with), and another one called lead score (a score given to the demographic value of a lead).

But these metrics can be misleading for several reasons.

1. Bias

It was very easy to bias our trial and lead scores.

For example, with trial score, which measures a user's engagement with a set of features, we could quite easily use our in-application tours to guide users to what we considered important features and thereby incorrectly influence this score.

Or we may have a belief that a certain type of lead is valuable, but not learn from past conversions on who is actually converting.

So our results were inconsistent and therefore unreliable.

2. Getting the wrong people in the trial

Trial score results also varied depending on who got into the trials. Simply put, if they were the right people (the right profile in the company, the right need, and coming in with the right expectations of value and effort), the scores were good; if they were the wrong people, the scores were not.

To be more specific, we got better results if we signed up people who:

- needed a service like ours;

- had the time and the technical skill necessary to create Klips; and

- had decision-making authority about spending.

On the other hand, results would not be so good if we signed up someone who was:

- too busy;

- had the wrong expectations about our value; and

- had no money to spend or was without spending authority.

And as we experimented with different lead generation techniques and advertising campaigns, the type of people who started trials varied considerably. Again, it was hard to get consistent results. (Attribution has a lot to do with this as well, but that’s another topic.)

3. Managing changes in the application

The third problem was that changes in our application itself led to variations in trial results.

For example, we might introduce a new feature. We would then calibrate the trial to either score the users’ use of the new feature (or not) on the assumption that interacting (or not) with the new feature was an indicator of success.

Again, because we were changing the way we scored trials as we added or removed features in the trials, we were ending up with inconsistent results.

Why this matters

As any scientist will tell you, meaningful results need to be the result of controlled experiments. For example, it's critical to attract quality prospects — people who have a strong chance of converting into customers.

We would score prospects on things like job title (did it look like they had the authority to recommend a buy?) or the size of their company (Was it big enough to need a service like ours?).

We would try to figure out how engaged the prospects were, but in the end we were making assumptions about whether the person taking part in the trial was the right person.

Assumptions don’t make for meaningful metrics.

The conversion rate might be amazing if you get exactly the right people interacting with exactly the right features. But the simple conversion rate is not granular enough. It’s too far down the funnel to be meaningful. We needed something else.

In the end, we realized that the conversion rate was the wrong metric to measure if we wanted to understand and influence prospect engagement and quality.

True trials

We came up with a new way to measure the potential of a prospect converting to a client. We call it true trials.

The beauty of true trials is the simplicity of the concept:

If you get 1,000 people into a trial on Day One, it’s the 200 prospects who come back for Day Two that really count.

Those people — the ones who participate for more than a day — are more likely to convert into paying customers.

We now know we need to focus our efforts on attracting people likely to stick with a trial, and this means paying special attention to people who have gone beyond Day One.

As we began to use this true trials concept, the issues that had been annoying and confusing us fell away.

Even though there is a large decline in the number of people who do come back, the number of returnees is a very good and far less biased way of measuring whether we got the right people into the trials.

An important quality of the true trial metric is that it's an early predictor of conversion. Consider this:

It can take over 30 days for 80% of trials that will convert to actually do so.

This means that the earliest the trial conversion rate can be measured with any level of reliability is 30 days after the period of interest.

In the fast-moving world of digital marketing, that's very slow. But the true trial rate can be quite reliable even after just seven days.

In addition, the true trials concept gives us something very useful to measure.

For example, we can now set goals around generating 2,000 true trials each month or around improving our lead generation efforts so that we achieve above 25% of true trials to total trial starts.

Those measurable goals drive behaviour.

Before we started using true trials, we did as most companies do: we worked to drive traffic and leads, and if we increased the number of leads we thought we were doing a pretty good job.

But leads don’t mean anything if they don’t convert.

So with this newfound focus, Marketing is able to take a more targeted approach to the type of leads they're generating — leads with the attributes we typically see in those that make it to the second day.

And our UX and Development teams can start looking at what we have to do on the first day of a trial to increase the number of people who come back for the second day.

So we’ve stopped worrying about trial volume, and started focusing on true trials. We look at who they are, where they are, and what their journey is.

We are still experimenting, but our efforts are focused on what it takes to get people back after Day One.

How we got there

Though the concept of true trials is amazingly simple, simple does not equate with obvious.

In fact, we struggled with how to predict the conversion of prospects into customers until one of our employees, Tomasz Ogrodzinski, stumbled quite serendipitously onto the true trials concept.

He was not specifically investigating trial efficiency; instead, he was trying to identify differences in behaviour between converters and non-converters.

In analyzing behaviours, one of the things he found was that a lot of non-converters had done almost nothing during their trials. As many as 80% of all the people logging in for trials were doing one or two things and never coming back again.

He raised the issue at informal chats in the company, initially calling the group ‘mayflies,’ in reference to the insects which, in their adult form, live only a few hours.

We started tracking the number of ‘mayflies’ in our trials.

At one point, we realized the number was significant. The ‘mayflies’ were not really interested in our product. They either did not understand what the product was, or they were a poor fit.

Unsurprisingly, they almost never converted. Yet because of their large numbers, they had a huge impact on our overall conversion rate figures.

The true trials, on the other hand, were coming back and giving the product an honest try. The conversion rate in this group is extremely good compared to our overall conversion rate.

So when the true trial rate goes up, the overall conversion rate goes up as well... and we can predict this far sooner in the process.

The beauty of simplicity

In addition to being an easy, valid measure of the likelihood of a prospect converting to a paying customer, the true trials model offers one other benefit: It’s very easy to explain.

And because it’s easy for everyone in the company to understand, it’s easy for everyone to rally around.

Its simplicity also speeds up the process of calculating win rates.

As I mentioned previously, prior to developing the true trials measure we had to wait at least 30 days to calculate the likelihood of someone who entered a trial converting to a paying customer.

The true trials measure now allows us to estimate much more quickly — sometimes within as little as two to seven days — whether a trial will convert into a customer. It's an early indicator of the win rate.

Conclusion

The metrics you use to evaluate your performance have to be meaningful to you.

If those meaningful metrics are not available, take the time to create your own.

It may take a couple of tries to find something that resonates.

You may also have to work to convince people in your company that the new metric is truly meaningful — and truly useful. (We did have to do some internal marketing to convince people inside Klipfolio of the value of true trials.)

But do it right, and your own home-grown metrics might become the new industry standards.

Allan Wille is a Co-Founder and Chief Innovation Officer of Klipfolio. He’s also a designer, a cyclist, a father and a resolute optimist.