Implementing OKRs, faster, cheaper, better – and easier

Published 2023-02-01

Summary - The fastest, cheapest, best, and easiest path to OKR success is through motivating, educating and triggering OKRs in the organization.

Executive Summary:

The issue with OKR implementation is the same as any other change – but worse! What OKRs add to the normal change issues is…ego. Because OKRs effectively dissect what we do down to crisp Objectives and “as measured by” specific Key Results, they, to some extent, put our activities under a microscope, hence ourselves under the same microscope. Naturally people begin to pay very close attention.

Recognizing this does not make OKRs impossible to implement – but it does inform us of things that we should uniquely consider while implementing them.

This article is largely about applying BJ Fogg’s Behavior Change model to OKRs. His theory, restated by me, as applied to OKRs is a bit like this:

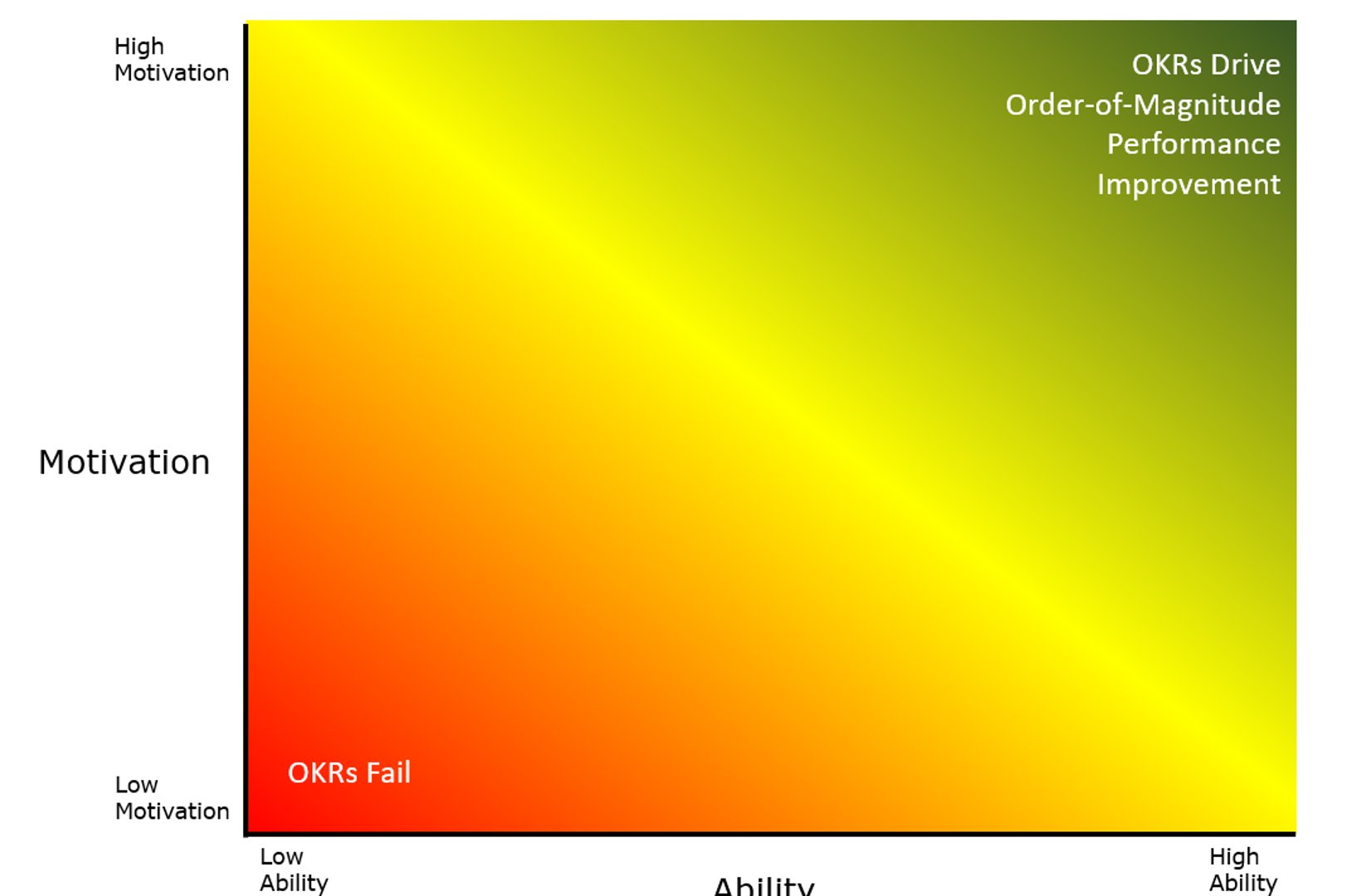

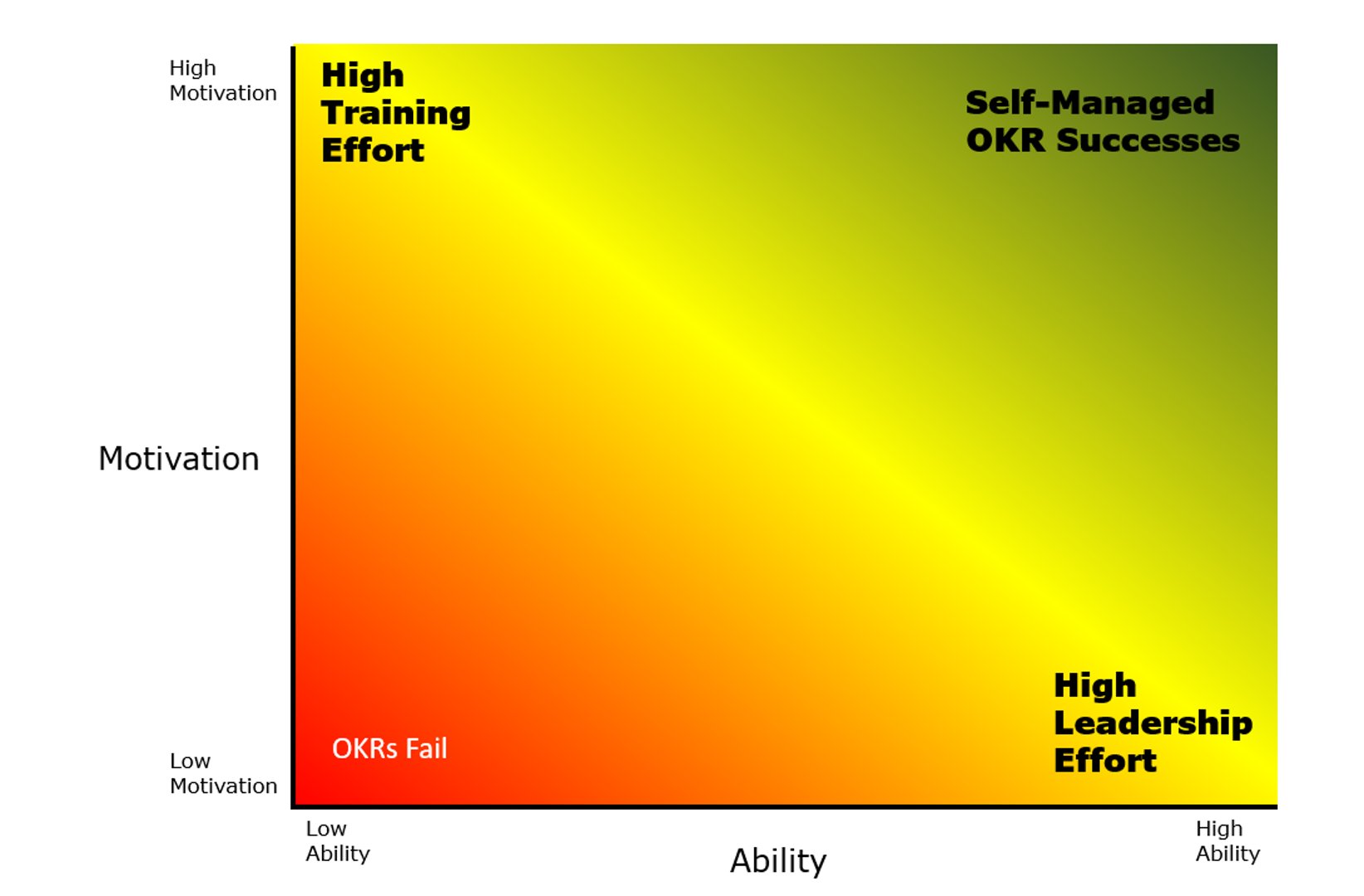

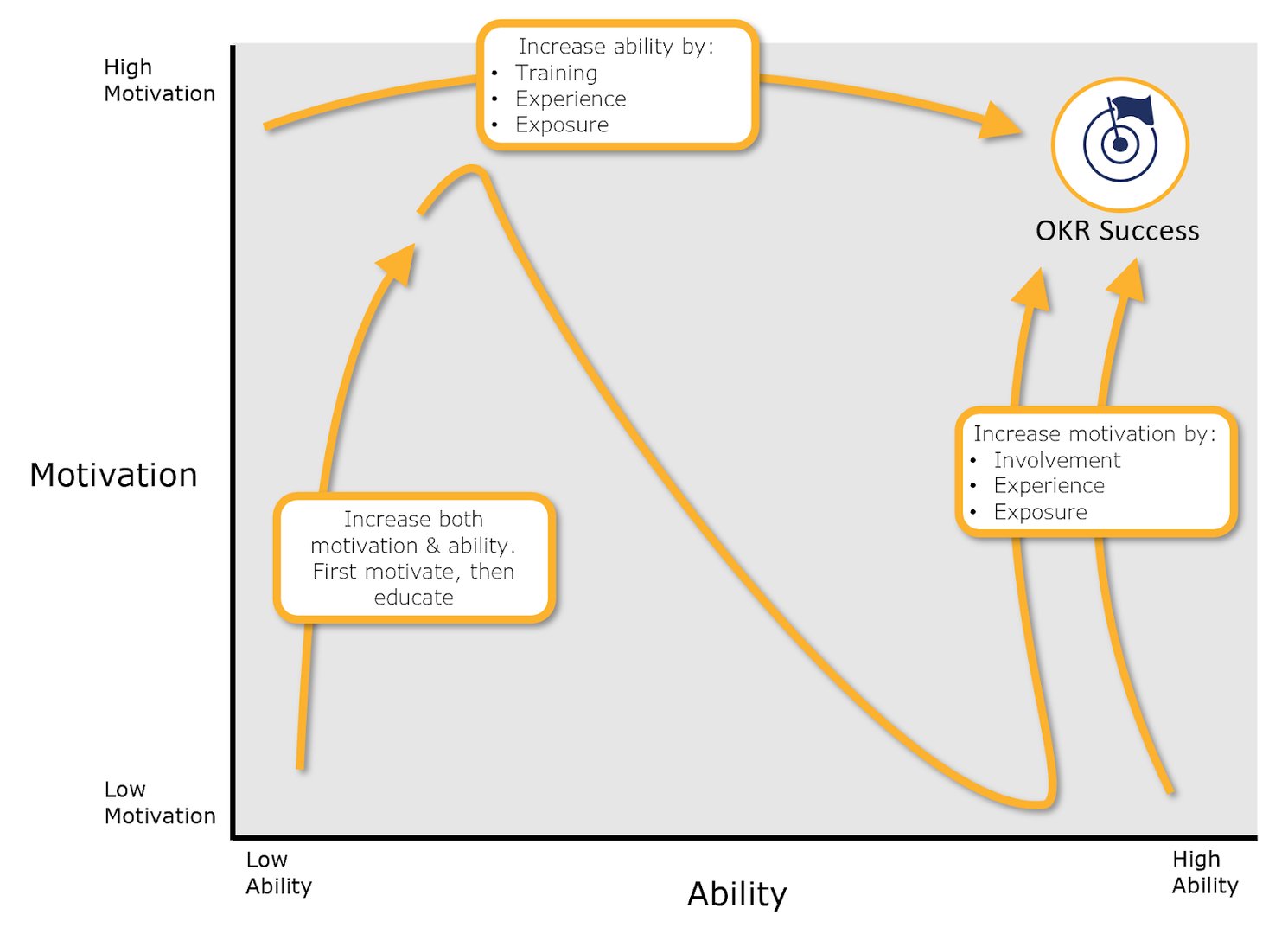

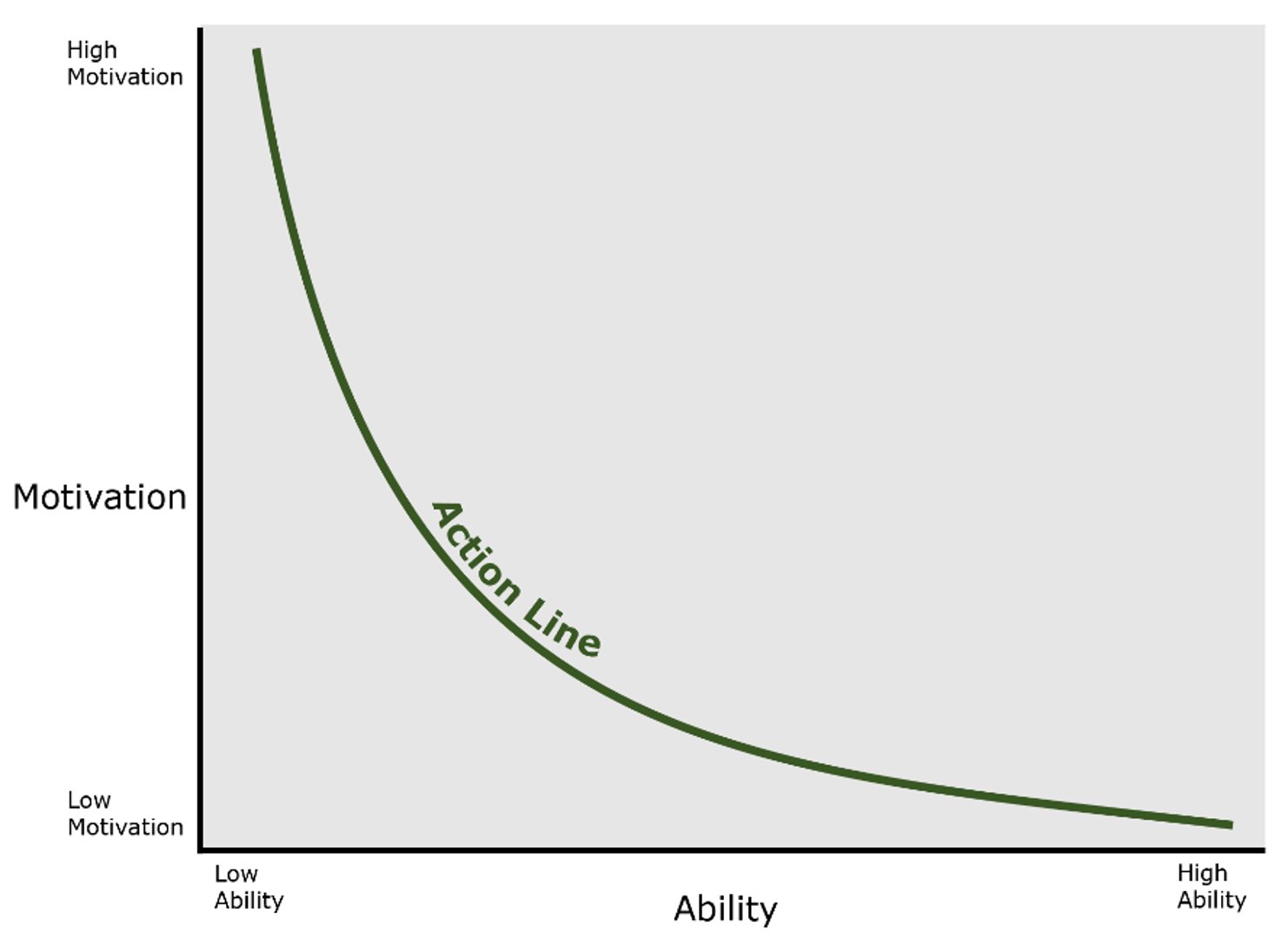

The extremes of this chart reveal the effort type and level to make OKRs work:

The fastest, cheapest, best, and easiest path to OKR success is through motivating, educating and triggering OKRs in the organization.

So, to cut a long story short, your strategies are straight forward:

To implement your OKR solution – faster, cheaper, better and easier, all you have to do is:

1) Assess your organizations OKR-motivation level

2) Assess your organization’s OKR-ability level, and

3) Set the right prompt strategy

The rest of this article goes into enough detail to explain these elements and then a “how-to” apply this framework the ensure your OKR implementation success.

The BJ Fogg Behavior Model

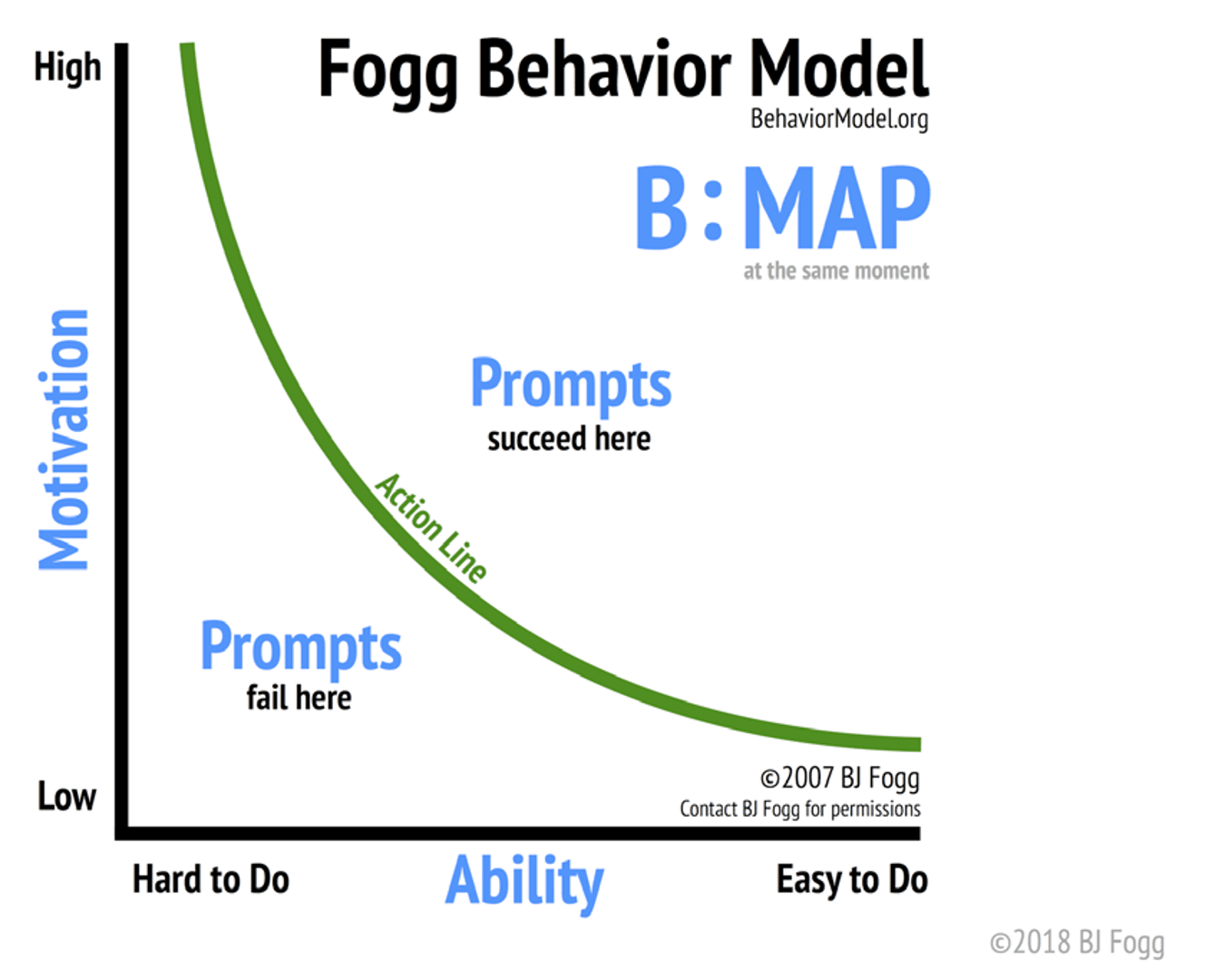

The underlying logic to this article comes from the insightful work of BJ Fogg and his Behavior Model.

The Fogg Behavior Model (FBM) highlights three principal elements as the drivers of behavior. The FBM outlines Core Motivators (Motivation), Simplicity Factors (Ability), and the types of Prompts.

The FBM shows how behavior is the result of three specific elements coming together at one moment. In addition, the FBM shows that Motivation and Ability can be traded off (e.g., if motivation is very high, ability can be low). In other words, Motivation and Ability have a compensatory relationship to each other.

This framework has been widely applied and proven to be valid in multiple situations.

What causes behavior change with respect to Performance Management?

1) Motivation — People have to be sufficiently motivated to want to manage their and their team’s performance.

2) Ability — They must have the ability to develop OKRs, monitor performance and manage with them, and

3) Trigger — There needs to be a trigger or prompt to encourage the change in behavior.

If one of the elements is missing, behavior won’t happen. Another way to say this is as follows:

B = MAT (Behavior = Motivation + Ability + Trigger)

Overview of the Fogg Behavior Model

Here are four things you can notice right away about the Fogg Behavior Model from looking at the graph:

1) As a person’s motivation and ability to use OKRs increases, the more likely it is that they will use OKRs.

2) There’s an inverse relationship between motivation and ability. The easier it is to implement OKRs, the less motivation is needed to use them. On the other hand, the harder they are to implement, the more motivation is needed.

3) The action line—the green curved line—lets you know that any behavior above that line will take place if it’s appropriately triggered. At the same time, any behavior below the line won’t take place regardless of the trigger used. Why is that? Because if you have practically zero motivation to use OKRs, you won’t regardless of how easy it is to do. At the same time, if you’re very motivated to use OKRs, but it’s incredibly difficult to do, you’ll get frustrated and you won’t act.

4) If you want OKRs to succeed, look for ways to boost motivation or ability (or both). In other words, aim for the top right of the model.

Elements of The Fogg Behavior Model

Motivation

Most of us know that we need to have some degree of motivation to successfully take action, such as to complete exercise programs or stick to a diet.

I see motivation as “the internal process which directs our behavior”. It determines what we want to do and why we feel like doing it.

Core OKR Motivators

Internal vs. External Motivators

In his book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Daniel Pink proves that external motivation (e.g. rewards from your boss) can be successful in repetitive, low cognition tasks, but that external motivators have little or negative effect when it comes to more complex tasks and long-term behavior.

Intrinsic motivators are things that you enjoy yourself. If you play sports, a musical instrument or even video games, you do so for the intrinsic rewards – how they make you feel good by doing them. No need for outside affirmation.

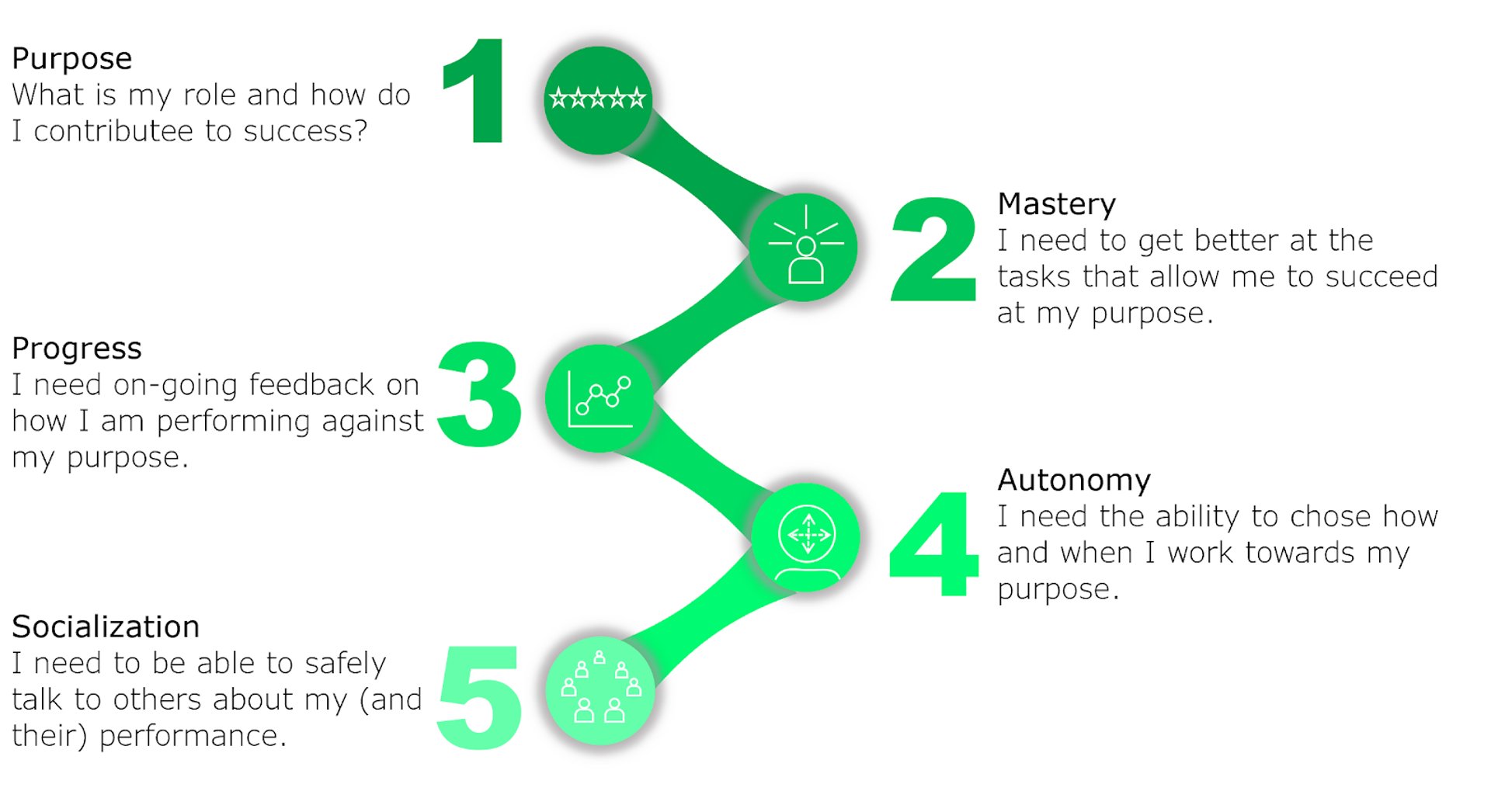

Daniel identifies three internal, or intrinsic, motivators for modern-day complex jobs – the typical jobs we see in high-tech and contemporary organizations. Our experience has caused us to add two more for OKRs.

Success in OKRs come from leveraging all five of these intrinsic motivators. If you and your co-workers can see how OKRs help them achieve all five of these motivators, your OKR solution will thrive.

Here they are (in no particular sequence):

Purpose – “I make a difference”

Every employee needs to understand:

OKRs deliver “purpose” to every employee by clearly defining their Objectives and how they can measure their progress around them – Key Results.

Mastery – “I improve”

Employees want the opportunity to improve because:

Your organization has to provide this – the learning, experiences, mentoring and coaching to help them get better.

Progress – “I achieve”

It is amazing how few modern jobs provide on-going (moment-to-moment) feedback on how we are performing. Progress reports (dashboards, scorecards, etc.) allow:

OKR solutions provide this through the on-going performance reporting.

Autonomy – “I control”

We like the opportunity to chose when and how we complete our responsibilities

OKRs enable autonomy as they direct employees towards Objectives and not tasks.

Social Interaction – “I connect with others”

We are all social to some degree – we need to connect, care and share. Within our peers, we also want to be recognized , be understood, and understand.

The sad part is that in business we tend to have infrequent performance conversations and invite a limited number of people. Most employees to not have frequent and open conversations about performance – theirs or the organization’s. They are not recognized, understood or understand.

A core part of all OKR solutions are the on going performance conversations and open sharing of information.

OKR Motivation Check-List

There is a logical sequence to building your intrinsic OKR motivators.

1) Develop the OKRs to clearly define the department/team/individual’s purpose

2) Develop the training, experience, mentorship and coaching to help people master the required skills

3) Your OKR solution needs to provide frequent, on-going, progress and performance feedback,

4) With a clear purpose, the right skills, frequent feedback, you are now ready to be autonomous in your decision making, and

5) You can now enable meaningful conversations across the organization

Ability

So what do we mean by ability? I like to define it as the ease in which you can complete an action. It is a combination of your skillset with the difficulty of the task at hand.

Why does ability matter when implementing OKRs?

To illustrate, let’s consider the seemingly simple act of going to your first OKR design meeting. We might have it in our calendar (be triggered…covered next) and want to go (have the motivation…covered before), but chances are we still won’t go if some external factor has decreased our ability. For example, if your boss has not expressed interest or your teammates are not going. Either way, something has made it very difficult for us to get our butts into the meeting room

It can also be that the challenge of setting up OKRs itself is too difficult or that we perceive it to be. Here it is helpful to imagine our level of ability being on a spectrum from very hard to very easy.

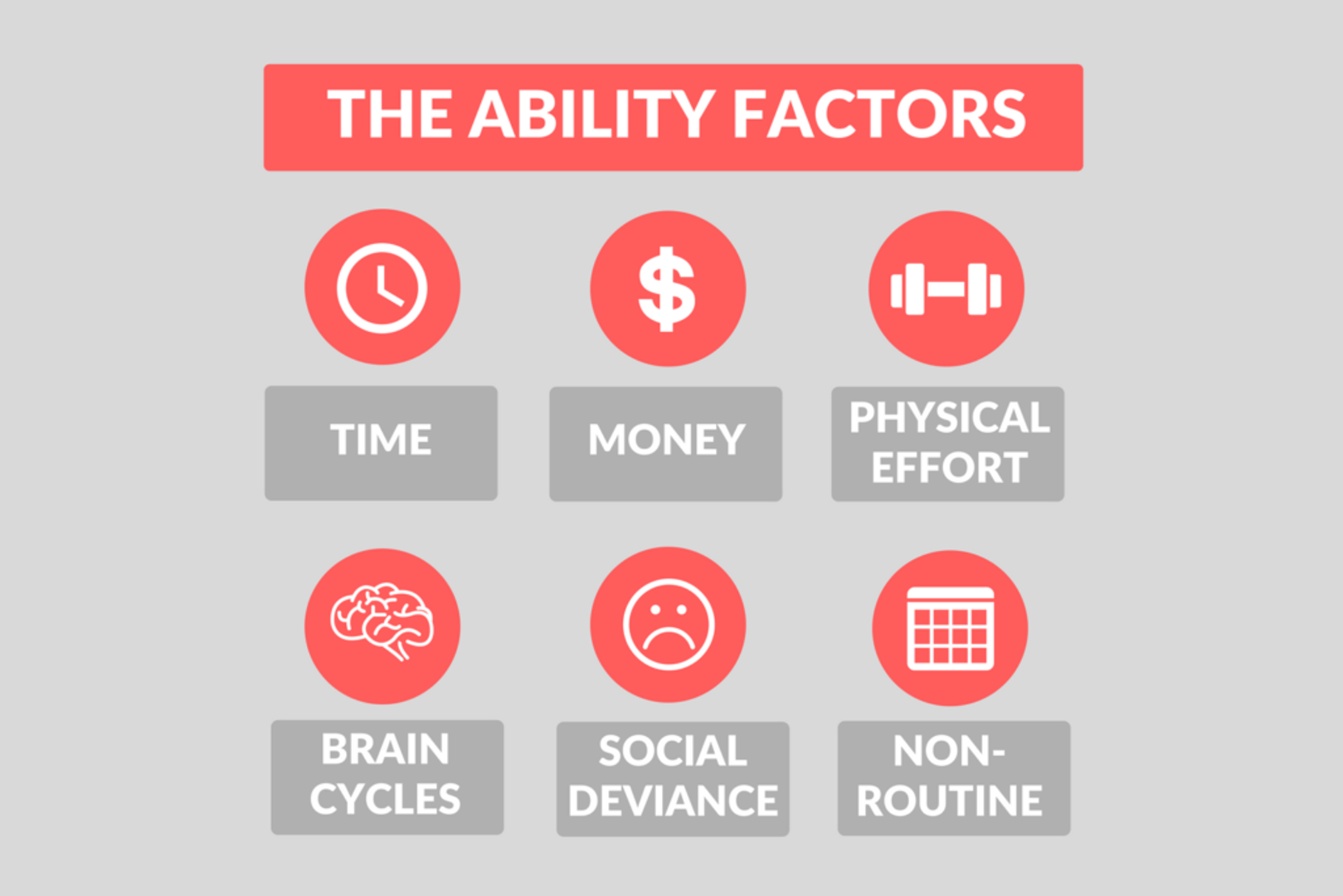

Ability Factors

Again, our hero Stanford professor and perhaps the godfather of behavior design, BJ Fogg, comes to our rescue. BJ has identified six components of ability. Like most resources, these factors are also limited and often in short supply.

Here are the six ability factors:

1) Time: The time it takes to complete the behavior.

2) Money: The money required to complete the behavior.

3) Physical Effort: The physical effort required to complete the behavior.

4) Brain Cycles: The mental effort required to complete the behavior.

5) Social Deviance: The degree to which the behavior requires you to do something out of the norm.

6) Non?routine: The degree to which the behavior requires you to do something outside of your current routine.

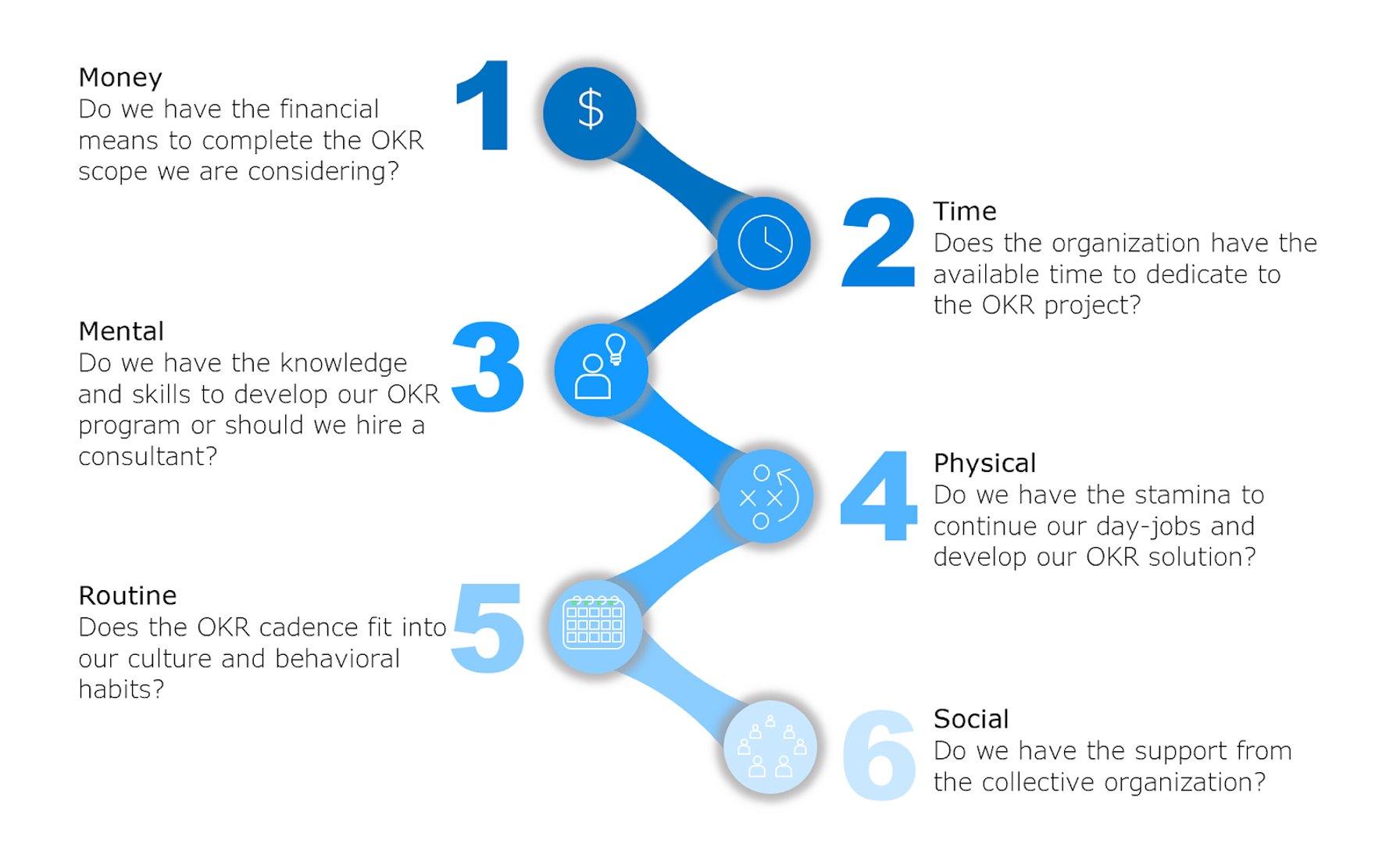

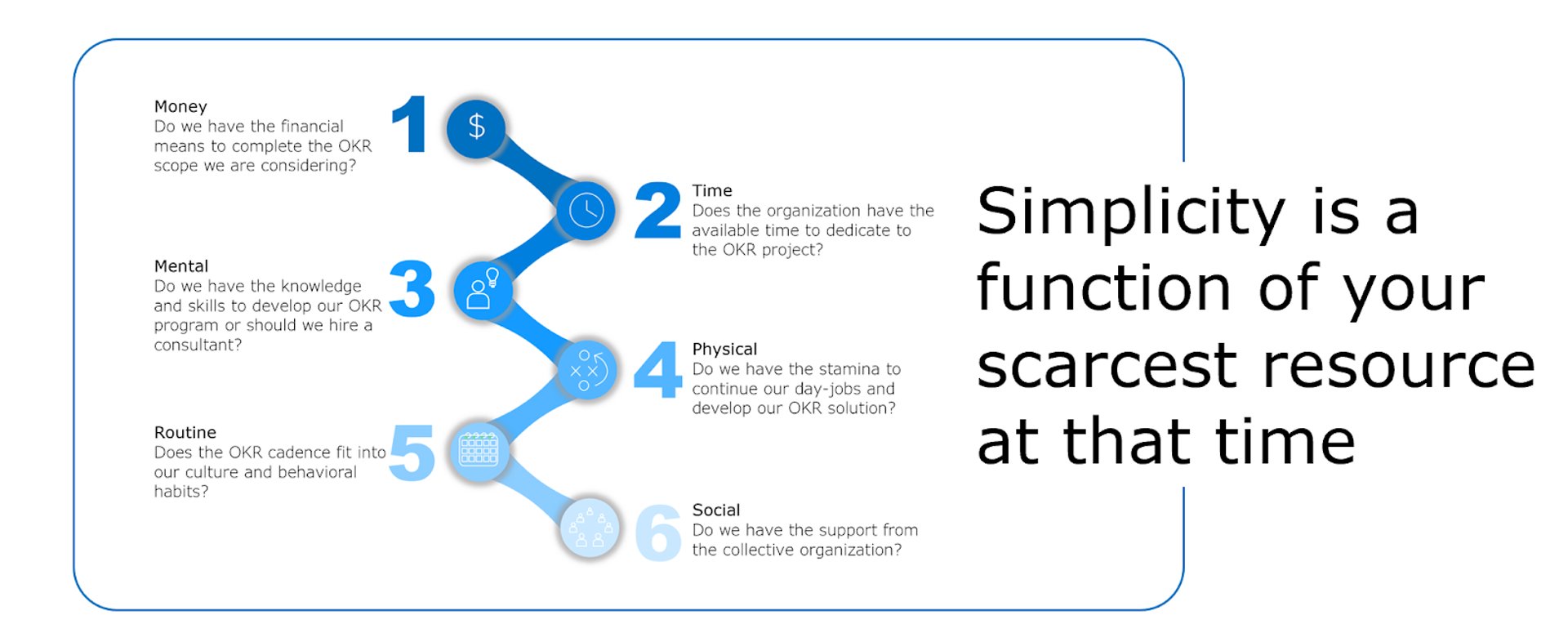

So what happens on our OKR journey is that the ability is a function of a person (or team’s) scarcest resources at that moment. So we can increase our ability to implement OKRs we simply need to identify which Ability Factor(s) are most scarce, and then find ways to use less of them.

Let’s look at how an organization can implement OKRs by making the job easier.

1) Time: How much time do I have to build my OKR solution?

Many organizations most common excuse is that “we don’t have time.” Time is indeed finite, but while we don’t have all the time we want, we often have enough time to do something.

If setting up the full OKR system takes too long, then we could implement it in one area. If we cannot implement it in an area, how about a team? An individual? Something is always better than nothing, and even a small team can make a huge difference in the long-run.

2) Money: Can the organization afford to sustain the new OKR behavior or habit?

As with time, money is a common constraint and excuse concerning OKRs and performance improvement. Some OKR regimes and consultants indeed require a “healthy” outlay of funds.

If this is the case, then what would be a more affordable alternative? Unfortunately there are no “How To” OKR books published yet, but there are User groups, or you can leverage OKR YouTubes, many of which explain methodologies. There are also workshop- formatted programs that can be categorized as training and therefore offer tax and expense off-sets.

3) Physical Effort: How much physical effort is required?

Luckily, OKR implementations are light in this category! No need for any physical effort. Designing, building and implementing an OKR solution should take no more than a few days – so the need for stamina is not significant.

4) Brain Cycles: How much mental effort is required?

The mental effort of building an OKR solution may be too high for some organizations. You’d rather spend your brain cycles on developing new products, selling more stuff, or meeting more customer needs. It is also possible that you are starting from a weak place – you don’t have a defined strategy, you are unclear on who does what.

One client once said to me “I am so busy bailing that I do not have time to turn off the tap”. Making time to turn off that tap is critical.

You can use less brain cycles by:

5) Social Deviance: Is the entire organization and network supporting or stopping you?

Most are familiar with the idea that we are the average of the five people we spend the most time with and this is also true for OKRs. If none of your customers, suppliers or partners are focused on performance, then it will naturally become harder for your organization. And the opposite is also true.

Again, User Groups and peer support are helpful.

6) Non?routine: Are performance conversations and focus a part of your current routine?

Are you already routinely having performance conversations? If not, it is important to consider how you will connect an on-going performance awareness to the organization’s current routine. When and after what current habit do you plan to talk performance?

The take-away

By tweaking each of these factors, we can make developing an OKR system and habit much easier and in turn much more likely to succeed.

The goal here is to make doing your behavior ridiculously easy.

Going through these factors can be done for any behavior and can have an incredible effect.

Simplify

One common mistake in creating OKRs is making things too difficult. We try to get the perfect OKR from the beginning, we try to get everyone on OKRs right away, we try to cascade OKRs down to the individual in the first pass. We put ourselves through grueling regimes or try to quit all of our bad habits at once.

We go so far beyond our normal ability that we often need to patch up the gap with motivation. Unfortunately, motivation is cruel and will turn on you at the flip of a dime. It will be there one week, but then disappear the next. This is why four out of five OKR attempts not only fail but lose any performance achievements they made (and then some).

We are better off simplifying our approach and starting small. Once we begin with an OKR habit or behavior that we can sustain, we can then incrementally increase difficulty over time.

These are two of the golden rules in behavior change: Make it simple and start small.

We dramatically increase our chances of success if we start with something that is relatively easy, that is, something we can do even on a bad day. Then as we get into the habit of doing it, we can increase the difficulty and make it more challenging as time goes on.

Ability checklist for your OKR Solution

Prompts

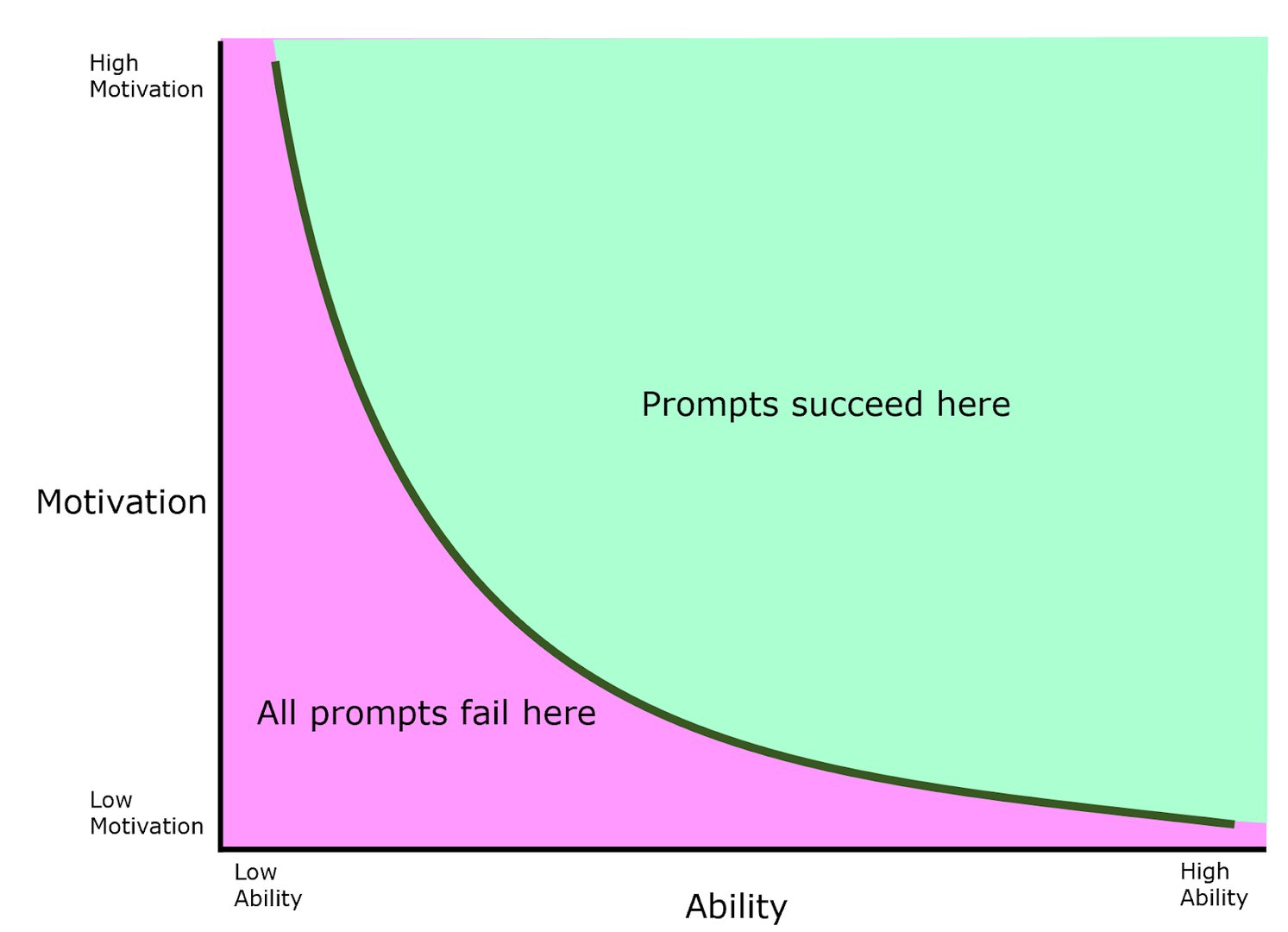

So all this is fine – two axis chart that makes sense.

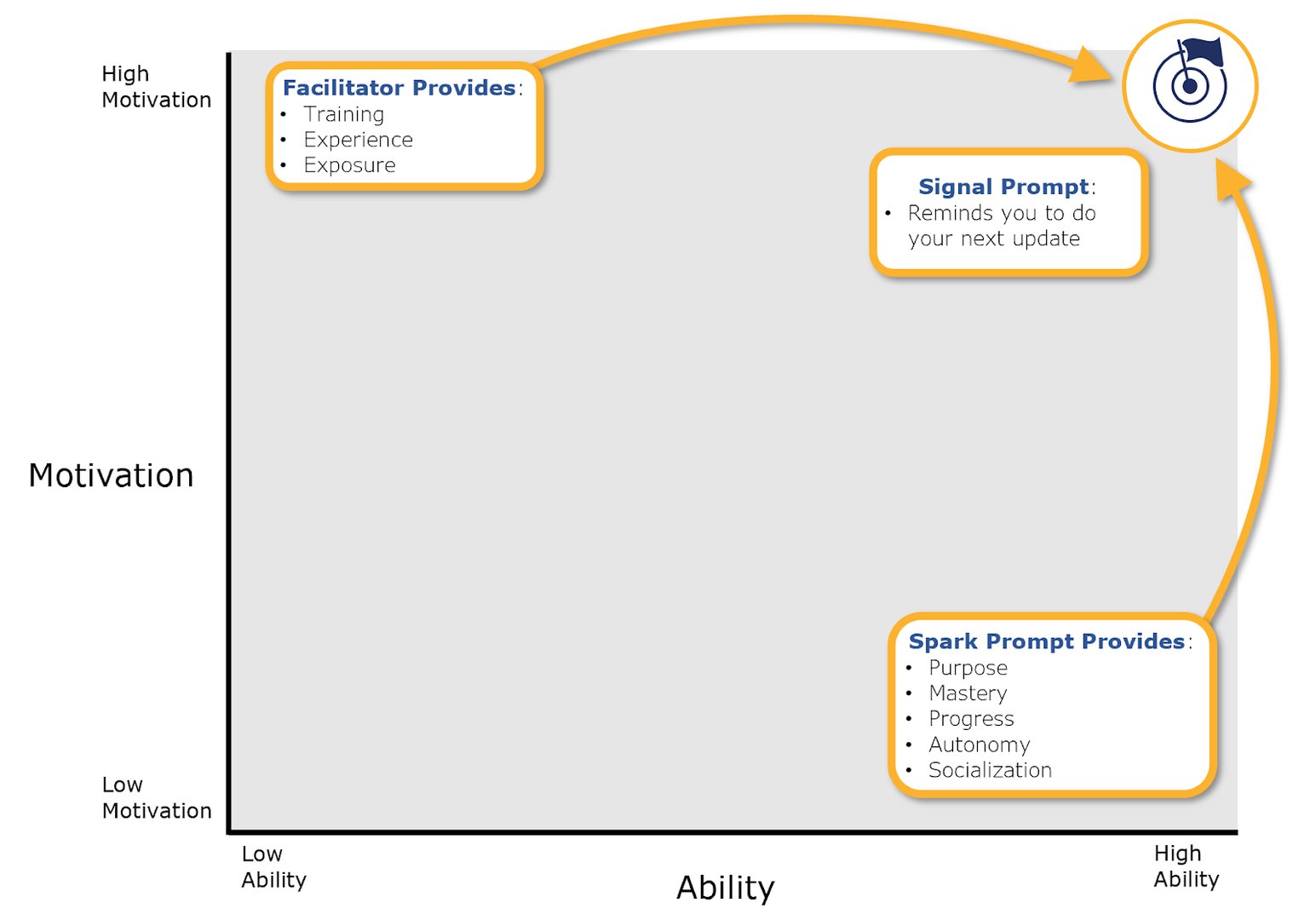

Now comes the tough part. To make change happen, we need a prompt – something to cause us to change (i.e. implement OKRs). In the top right corner – high motivation and high ability, we do not need much of a prompt. As we fall off in either motivation or ability, we need a high force of a prompt required to make the change happen.

In the OKR context, the higher the motivation, the lower ability the organization needs to succeed with OKRs. The opposite is also true: The higher the ability, the lower the motivation needed to succeed with OKRs.

We actually end up with an “action curve” that looks like this line:

In fact it creates a “likelihood of success curve”

A prompt is best described as call-to-action. A prompt could be as simple as leadership asking us to build an OKR solution. A more significant prompt could be on-going OKR meetings, even larger, rewards for getting the OKR system running, etc.

So let’s now dig a bit deeper into OKR prompts and see why they matter in OKR implementation success.

Internal vs. External Prompts

The most important distinction to make with prompts is the difference between external and internal prompts.

External prompts are anything in your environment that tells or remind you to do something. It could be a post-it note, a billboard, or a phone notification. It is something external nudging you to do something.

For OKRs it could be the automated reminder from your OKR tool, your weekly performance meeting or an updated scorecard.

Internal prompts are any feeling or emotion that tells or remind you to do something. Typical examples of this are feelings of hunger or thirst. It is some signal from your body nudging you to do something.

In the OKR world it becomes your daily performance habit, your desire to see how you and your team are performing and your need to update your team on your progress.

Types of External Prompts

Stanford professor BJ Fogg has identified the following three types of external prompts:

Spark: Helps when you have the ability, but not the motivation. An example of this is a reminder to go to the dentist. The reminder sparks you to get ready for the appointment, even if you are not currently motivated to go.

Facilitator: Helps motivated people who lack the ability to complete a behavior. Facilitator prompts make the action easier or at least seem easier. A typical example of this is the instructions to help you write your OKR analysis.

Signal: Helps people who are both motivated and have the ability to complete a behavior. The primary purpose of the signal trigger is to remind us of something we want to do. An example is a calendar reminder for your next OKR meeting.

Master The Force

When you start understanding this concept, you begin to realize that there are prompts all around us. Our alarm clock, our Facebook notifications, our inbox alerts, our hungry stomachs, and the list goes on. Hundreds of prompts gently nudge us along and shape our OKR routines.

Part of making a great trigger is understanding the context (spark, facilitator, and signal) and then determine a suitable frequency of how often the prompt should occur. The mix of prompt type and frequency is a fine art…in every instance except OKRs. In the OKR world it is pretty easy to sort out your organization’s ability and motivation levels. From there it is a short step to sort out the best prompt and frequency.

So this is where this story ends – to make sure your OKR solution works – faster, cheaper, better and easier, all you have to do is:

Related Articles

2025 BI and Analytics Trends for Small and Mid-Sized Businesses

By Allan Wille, Co-Founder — December 18th, 2024

Let’s fix analytics so we can stop asking you for dashboards

By Cathrin Schneider — September 11th, 2023

Guide to migrating your digital marketing dashboards to Google Analytics 4

By Jonathan Taylor — February 13th, 2023